Think INSIDE the box

Be very careful when thinking outside the box. (5 min read).

“Think outside the box!” I have heard that so many times I might puke. What does it even mean?

Often the phrase is just misused to mean “be smart” – which is stupid. But fundamentally thinking outside the box is about ignoring rules. Or rather, to realize that there are no rules in the first place. A good example is the “Columbus egg”:

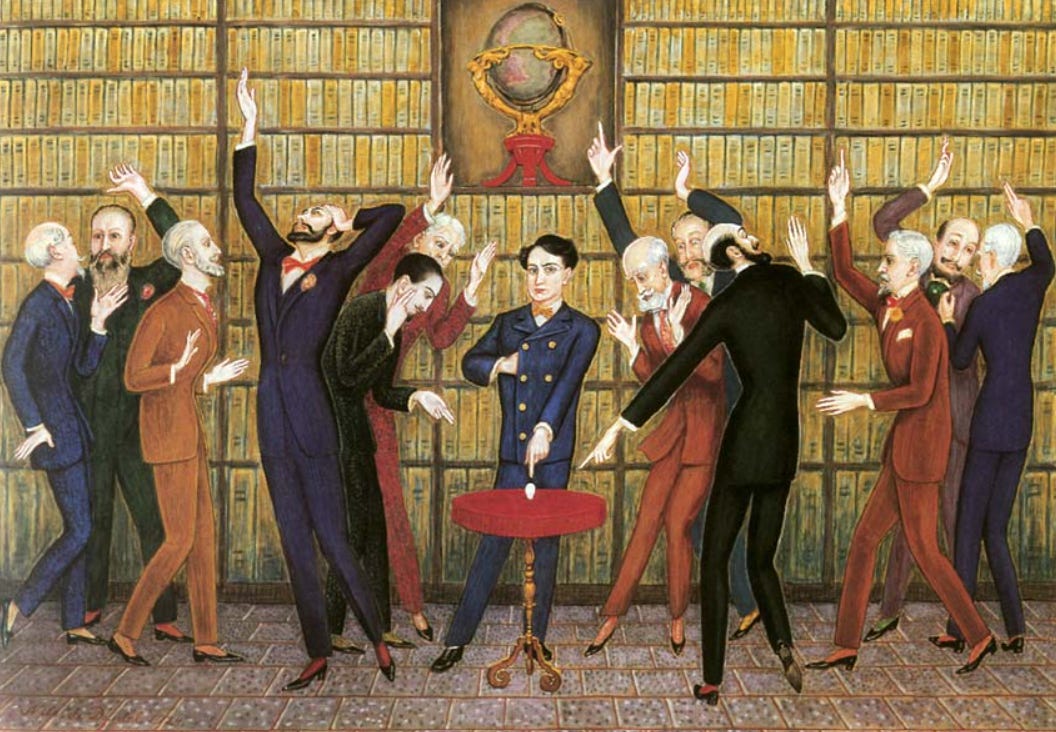

According to legend – which is almost certainly no more than that – Christopher Columbus had returned from his discovery of the New World and was at a party. Some of the guests mocked him for making such a simple discovery. “Just sail west! Nothing complicated in it! Anyone could’ve done it!”

Columbus took an egg and challenged the mockers to balance it on a table with the tip upwards. No-one could do it. Columbus then took the egg, knocked it hard into the table, flattening it on one side so that it could easily stand upright.

Columbus broke the rules by breaking the egg. Or more precisely, he showed that there was no such rule to break. The mockers had just assumed they weren’t allowed to break the egg. Or the metaphorical box.

But why did the mockers assume there was such a box? Because they were human. We like boxes, and live most of our lives in them.

Columbus demonstrated the folly of this. Or… Did he really? In fact, all he showed was that such box-thinking was foolish in that particular situation. It is even possible to draw the exact opposite conclusion of the demonstration – not that thinking inside the box is bad, but that it is good. This is because such inside the box-thinking is so common that there must be a reason for it – we humans wouldn’t have survived if there wasn’t.

Consider this experiment: Psychologists presented chimpanzees and children with a (real) puzzle-box. Using a stick and poking the box in the right way, the chimpanzees and children could access sweets inside it. The psychologists showed the chimpanzees and children how to open the box, but added a twist: they tapped the box a few times. These taps had nothing to do with opening the box. When the chimpanzees were allowed to try after seeing this demonstration, they ignored the taps but followed the other instructions. But when the children tried, they also imitated the taps.[1]

We humans are not as intelligent and creative as we think we are. Instead, we are really good at imitating each other. This is not the same as intelligence, in fact, intelligence can interfere with imitation if it makes us less obedient. This unthinking rule-following is so important to humans that we, like Columbus’ mockers and the children with the puzzle-box, often do it even when we shouldn’t.

Imitation is the cornerstone of all civilization. We invent rules, sometimes explicit but more often implicit, and follow them. These rules make up the boxes in which we live, such as countries, cities, corporations, institutions, clubs, families, schools, parties, sports, professions and artforms. Some boxes are large, and other boxes are small. Often the smaller boxes fit inside the larger boxes. With these boxes we both order and create our world, keeping chaos at bay.

One of the reasons we like boxes is because they allow us to focus our efforts. We can’t know everything, or even a millionth of everything, which means that we must intentionally ignore many things outside the box. A good example of this is sport.

Sports are boxes, very well-defined boxes with clear rules and standards. Runners are supposed to run fast, high-jumpers jump high, and powerlifters lift heavy. This creates small boxes inside of which we can specialize, which in turn gives us a sense of control. In sports, we have clear purpose and know what is good. That makes sport enjoyable. Those who think outside these boxes are (rightly) condemned as cheaters.

But not all boxes are like that, and their borders constantly change. When boxes are more fluid, it is called “freedom”. It is a great and terrible thing. Great because it allows us to do what we want, terrible because we do not know what we want. It places us face to face with the vast inscrutable complexity of the world. The solution must inevitably be to create new boxes, such as corporations, clubs or families.

Like so many things in this world, thinking outside or inside the box is a matter of trade-offs. There are advantages to both. But most of the time we should be inside our boxes, since it is just too dangerous and chaotic outside of them. A civilization is a set of boxes inside boxes, and whatever its flaws, we quickly learn to miss it if it collapses into anarchy.

But sometimes we must head outside the box and into the unknown. Either to explore the unknown, or because the old box just doesn’t work anymore. Either way, the goal is to create a new box, a better box, a larger box, rather than to get rid of boxes entirely.

The people who step outside the boxes and succeed are hailed as geniuses and prophets. But the vast majority who step outside the boxes are just ordinary criminals, dropouts and lunatics. Geniuses are geniuses not because they stepped outside the box, but because they got away with it.

Jakob Sjölander

[1] Daron Acemoglu & Simon Johnson. Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity. Basic Books. (2023). Chapter 3, section “Agenda Setting,” page 77.