We need each other like fish need water

We humans create our own environments from each other. (4 minute read).

Alone, we humans are pitiful creatures. Our brains contain just a single gigabyte of knowledge.[1] A modern smartphone easily contains a thousand times that. The little knowledge we do possess depends largely on our cultural environment. What people have told us, what we have seen on television, read in books, and suchlike.

As individuals we know many things, such as that the earth is spherical, that it revolves around the sun, that Paris is the capital of France, that there once upon a time was such a thing as a Roman empire. But few of us have really checked these things ourselves. Naturally, we could find verify it if we had the time and will, by studying astronomy or visiting Paris. But for the most part we don’t. We trust what we have been told. We don’t have a choice – there just isn’t time to become an expert in every field. Luckily this trust, it must be noted, is generally justified.

Consider these words of Saint Augustine, written around 400 AD:

“I began to realize that I believed countless things which I had never seen or which had taken place when I was not there to see – so many events in the history of the world, so many facts about places and towns which I had never seen, and so much that I believed on the word of friends or doctors or various other people. Unless we took these things on trust, we should accomplish absolutely nothing in life.”[2]

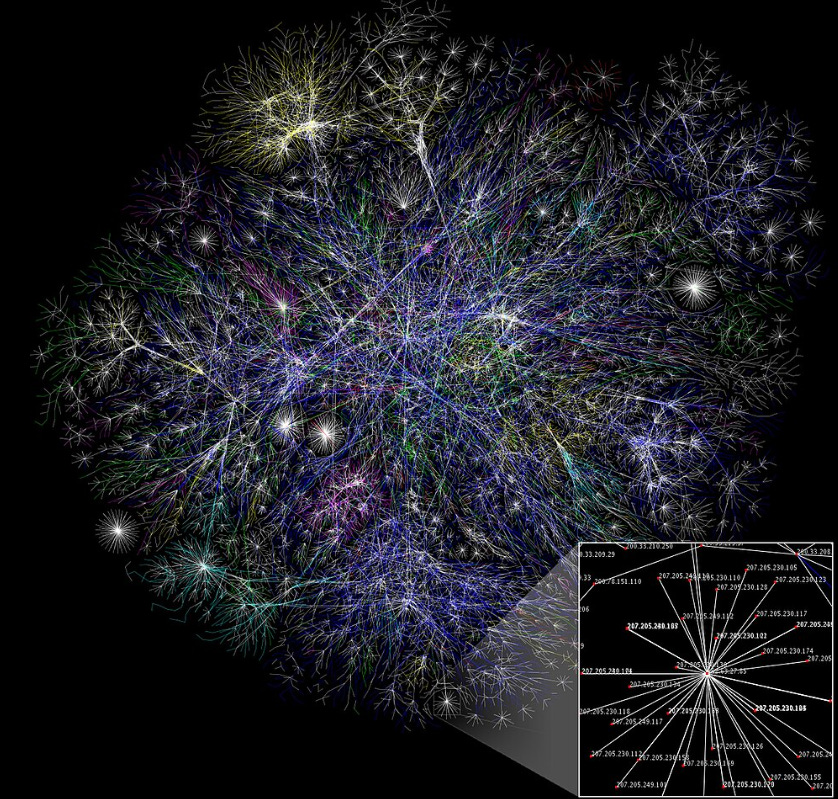

Knowledge, intelligence and reason are primarily social things. We need a community to partake in it, or at least indirect access to such communities through reading. A single human is just as lost and ineffective as a single ant or bee.

This is true of us even in our most primitive conditions, where we live in bands and tribes consisting of friends and relatives. We are a social species, and the environment we have evolved to live in is the social environment. This is why humans are pretty much the same all over the globe, no matter how different the physical environments we grow up in are. What matters is the social environment.

Today, we humans are completely dependent on each other. But this is not something new. This has been the case for humans and even pre-humans for hundreds of thousands of years, and probably millions. We rely on culture rather than biology for survival.[3]

Alone in the wilderness, humans do not survive for long. At least if we lack tools and technologies, which we cannot make on our own. Even the most skilled survival experts do not make it long term in the wilds when their ammunition runs out and their knives and axes rust away.

Our adaption to a social environment is well illustrated in a 2007 study comparing the intelligence of toddlers, chimpanzees, and orangutans. The toddlers were about two-and-a-half years old. As it turned out, it was a very even race. In tests of quantities and causality the chimps were actually a bit ahead of the toddlers. Curiously, despite our proud mastery of technology, the chimps scored 74% in test for tool use, while the toddlers only got 23%. Indeed, when it comes to things like working memory and processing speed, chimpanzees are quite able to hold their own even against adults.[4]

But the toddlers crushed the apes in one category – social learning. Basically, learning from others and mimicking their behavior. In that test they scored 86%, while the chimpanzees got 10%, and the orangutans 7%.[5]

It is easy to get arrogant when we see the achievements of our civilizations, with cities, science, and millions of people. It is easy to forget that each one of us only contributes a small piece to that, and that most of what we have was built by people now dead. We owe great debts to the work of our ancestors, far greater than we owe to our individual intelligence. Our knowledge comes from other people, and almost never from our own intelligence.

We need it each – just like fish need water.

Jakob Sjölander

[1] Steven Sloman & Philip Fernbach. The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone. Riverhead Books. (2017). Chapter 1, section “How Much Do We Know?”, page 25-6.

[2] Kathryn Schulz. Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error. Portobello Books. (2011)[2010]. Chapter 7, page 140.

[3] Joseph Henrich. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press. (2016). Chapter 17, page 316.

[4] Joseph Henrich. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press. (2016). Section “Memory in Chimpanzees and Undergraduates”, page 15-17.

[5] Joseph Henrich. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press. (2016). Section “Showdown: Apes versus Humans”, page 13-15.